If you'd like to receive

updates about the

Winter Solabration, please

A Short History of the Winter Solabration

Traditional American Community Dance

What is a Mummer’s Play, Anyhow?

The Evening’s Schedule of Events

39 Years! — Yikes! How could it be 39 years?

The instigator: 39 years ago, Karl Dise said, "Let’s have a big Christmas feast and party and dance." A bunch of friends got together and did just that — in 1985. We had music, dancing, and a feast. There was entertainment, too. The Maroon Bells Morris Dancers were in on this from the beginning. We also had some madrigal singers, a belly dancer, and a mummer’s play. And the Abbot’s Bromley Horn Dance and a surprise event. And we had so much fun, we did it all again the next year. The event has evolved and changed some since then, but here’s an overview of this year’s event.

The Winter Solabration is a celebration of the Winter Solstice in music and dance.  The dance consists of traditional American community dances — contras, squares, and a few circle and couple dances — all carefully taught and walked through so that all can participate. At the beginning of the evening there is wassail and community singing for everyone. Then there’s storytelling, a Grand March, dancing for all, and other special performances throughout the evening,

including a mummer’s play, and the Maroon Bells Morris Dancers.

The dance consists of traditional American community dances — contras, squares, and a few circle and couple dances — all carefully taught and walked through so that all can participate. At the beginning of the evening there is wassail and community singing for everyone. Then there’s storytelling, a Grand March, dancing for all, and other special performances throughout the evening,

including a mummer’s play, and the Maroon Bells Morris Dancers.

We loved the feast, and we did it for three years, but we soon realized what a huge amount of work it was. Thirty years ago, everyone bought a color-coded ticket with a recipe printed on the back. They made that dish and brought it to the event. If you prepared the mushroom casserole, for instance, a volunteer heated it in a microwave, and then put it in a chaffing dish and served it, along with all the other (presumably identical) mushroom casseroles. The organizers bought enough Cornish game hens for everyone, then got volunteers to thaw, split, and cook them, and they were served with Sauce L’Orange. Yummy!! But a totally huge amount of work requiring an entire fleet of volunteers. And then the clean-up! Cleaning the chafing dishes and silverware (you can’t have plasticware at a feast!) and packing them all up for a volunteer to return to the rental company. Cleaning all the casserole dishes and getting them returned to the owners (volunteers labeling and washing). Etc, etc, (whew!), etc.

It was great fun, but it soon became apparent that we needed to simplify things a bit. One of the most difficult parts was simply finding enough volunteers to do all the tasks. So the organizers (about 8 of us, at that time) plus a few volunteers, usually stayed up until about 4:30 a.m. getting everything cleaned and packed up. So the feast has evolved into a dessert or snack potluck. (Way easier!) The belly dancer and madrigal singers worked well when everyone was sitting down at the feast, but not so well when everyone was milling around the dessert-laden tables snacking and talking. We added a storyteller and a juggler when we realized that we didn’t have much for kids, and people wanted their kids to be a part of the event, too.

So now it’s been 38 years, and we’re still doing it. Amazing! Come and join us for this year’s 38th Winter Solabration — 6 to Midnight. Please bring a dessert or snack potluck dish to share.

A Short History of the Winter Solabration / What is a Mummer's Play, Anyhow? / The Rapper Sword Dance / Morris Dancing / The Abbots Bromley Horn Dance / Traditional American Community Dancing / Schedule of Events / Top of Page

What Is a Mummer's Play, Anyhow?

"In

comes I, Old Father Christmas.

Welcome in or welcome not,

I hope Old Father Christmas

Will never be forgot."

Who

are these characters? Why are they doing this? What does it all mean?

Mummer's plays originated in England, and were generally performed during

the winter months, often around the time of the Winter Solstice. The

first plays we have any record of were written down in the 1700’s, but

they were certainly performed before then. In fact, the lines are usually

in rhyming couplets as a memory aid, and existed in an oral tradition

harkening back to an earlier English pre-history. All mummer’s plays

have one theme in common: death and resurrection — the death of the

old year and the rebirth of the new. The dying and reawakening of the

earth, the triumph of light over darkness, of summer over winter.

Who

are these characters? Why are they doing this? What does it all mean?

Mummer's plays originated in England, and were generally performed during

the winter months, often around the time of the Winter Solstice. The

first plays we have any record of were written down in the 1700’s, but

they were certainly performed before then. In fact, the lines are usually

in rhyming couplets as a memory aid, and existed in an oral tradition

harkening back to an earlier English pre-history. All mummer’s plays

have one theme in common: death and resurrection — the death of the

old year and the rebirth of the new. The dying and reawakening of the

earth, the triumph of light over darkness, of summer over winter.

The earliest plays had a victim who was killed, and then magically resurrected. Sometimes the victim was one of the actors. Often, it was a slow-witted member of the audience (perhaps not entirely chosen at random). Although pagan in origin, after the Christianization of the British Isles, these folk plays absorbed or acquired many Christian characters. The hero often became St. George, and the villain became the Dragon. (St. George and the Dragon, of course, are linked to another early myth.) Old Father Christmas became a regular guest, who often introduced the other characters. This was the part played by the Broom in earlier plays, where the Broom comes to sweep out a space for the other players, and brings them in one at a time. Sometimes, Father Christmas and the Broom appear together.

With the Moorish conquest of parts of the Holy Roman Empire, the villain transformed into the Turkish Knight, or later, the Turkey Snipe. Political commentary was also a part of this tradition. Sometimes the players poked fun at the Lord Mayor, or the King, or the Privy Council. The appearance of the Doctor, who generally tries to heal the victim, and fails, was a commentary on the state of medicine in the 18th century, where you were just as likely to die under a doctor’s care as without one. (The odds didn’t really change for the better until the 20th century.)

One of the most important characters is the Clown, or Fool. After the Doctor fails at reviving the victim, someone has to bring him back to life again. Why does the Clown wield the magic? This may be a direct link to early Celtic shamanism, where the shaman was a divinely inspired madman — one who could break out of the patterns and unwritten rules of a culture. In other words, a clown — since only clowns have that power.

Other characters with links to Celtic pre-history appear in the mummer’s plays. In comes Molly, or Bess, the only female character, usually played by a man in a dress and shawl, representing the dual natures — the masculine and feminine aspects — of mankind. (Remember that no women appeared on stage in any role until well into the 1700’s. Early drama, with it’s links to magic, was considered to be the realm of men. Mummer’s plays, with their strong ties to ancient ritual drama, didn’t admit women as participants until the mid 1900’s.)

The Hobby Horse usually makes an appearance, often as the doctor’s horse. The Hobby Horse is one of the oldest characters, and is an ancient fertility symbol. There are entire festivals in Cornwall and Wales devoted just to the Hobby Horse. There he dances all day long, led by a Clown, of course, and accompanied by a band of musicians. In the mummer’s plays, the character of the Hobby Horse has been toned down, and perhaps lost some of it’s ritual power, but many plays still have one.

And there are a host of other characters, some of which appear in one play or another, or in one region or another. Some of them can pop up anywhere. A few of the more common ones are listed below.

In comes I, Beelzebub, with my pan, and my club — a wonderfully flexible

character. You can think of him as the devil, a representative of evil

forces, or as a personification of the nature God, Pan, who lived in

the forest and loved strong drink and wild parties. (Remember, it was

Pan who had the hairy legs, the cloven hooves, and the horns of a goat.

The devil only acquired them second-hand.)

Little Johnny Jack, with his family upon his back, usually represents the poor, or the homeless. He often begs for money at the end of the play.

The King, Queen, Sergeant, Captain, Groom, Old Dame, Boy Cupid, and others can also appear, along with sword dancers, musicians, extra clowns, politicians, and other villains. And all of the above can show up with different names. But someone always gets killed, and then brought back to life. Light triumphs over darkness, and life goes on.

— Chris Kermiet

Here's a link to an interesting site that includes the texts of many mummer’s plays: http://www.folkplay.info

A Short History of the Winter Solabration / What is a Mummer's Play, Anyhow? / The Rapper Sword Dance / Morris Dancing / The Abbots Bromley Horn Dance / Traditional American Community Dancing / Schedule of Events / Top of Page

It Ain't Rap, It's Rapper! — The Rapper Sword Dance

Dat

sword dancer, he sure look dapper,

If 'e talkin' like dis, maybe he be a rapper!

Lookit dat sword — can't be for protection —

Got a handle on both ends, it lackin' direction.

That

flexible steel — it can't be for stabbin' —

It made for dancin', it made for grabbin'.

Jes lookit dem go, jes lookit dem spin!

Dem sword dancers be rappin' again!

"Rapper"

may be a mutation of the word "rapier", or perhaps it comes

from "scrapper". Although the history of the rapper sword

dance is a little murky, it’s clear that the swords were designed especially

for dancing, and served no other purpose. They are constructed of flexible

spring steel, with a fixed handle at one end, and a handle that’s free

to rotate in the hand of the dancer on the other.

"Rapper"

may be a mutation of the word "rapier", or perhaps it comes

from "scrapper". Although the history of the rapper sword

dance is a little murky, it’s clear that the swords were designed especially

for dancing, and served no other purpose. They are constructed of flexible

spring steel, with a fixed handle at one end, and a handle that’s free

to rotate in the hand of the dancer on the other.

The rapper sword dance first arose in northern England in the towns along the river Tyne, and it was danced exclusively by miners, called pitmen. Why pitmen, and why only in this area? The answer may lie in the history of steel manufacturing in England.

Although there is an older sword dance tradition using metal longswords, they are heavy and inflexible with a handle at only one end. The longsword dance is slower and less flashy, but the figures have some similarities to the rapper sword movements. The earliest reliable historical report of a rapper sword team is from Earsdon about 1800. There are also records of dancers at Winlaton from the early 1800’s. There are some poorly documented reports of rapper sword dancing before 1800, but they may not be reliable.

Most British iron ore contains phosphorus, which makes it unsuitable for manufacturing steel. Early steelmakers in the mid 1700’s were importing Swedish iron to produce steel. It was made in small quantities and was too expensive to be easily purchased by the pitmen. Given these factors, and the scarcity of reliable records before 1800, most researchers conclude that the rapper sword dance probably evolved from an earlier longsword tradition in the late 1700’s, and was centered around the works of the best and largest steelmaker in Britain: Crowley’s on the Tyne river.

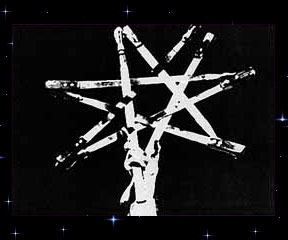

The

dance itself consists of a series of very fast figures where the dancers,

and the swords, weave in and out of one another, often forming "tangles"

of swords, which are then untangled by the dancers, who conclude each

figure by forming a "nut" or lock of swords, as in the illustration.

"tangles"

of swords, which are then untangled by the dancers, who conclude each

figure by forming a "nut" or lock of swords, as in the illustration.

The rapper sword dance was introduced in America before World War I, and is often performed here by Morris dancers, or by other groups who specialize only in sword dancing. Here, as in England, the dances are traditionally performed around Christmas time.

This year’s Winter Solabration will feature a performance by the Solstice Sword Dancers. This team has been performing the rapper sword dance together for over ten years.

A Short History of the Winter Solabration / What is a Mummer's Play, Anyhow? / The Rapper Sword Dance / Morris Dancing / The Abbots Bromley Horn Dance / Traditional American Community Dancing / Schedule of Events / Top of Page

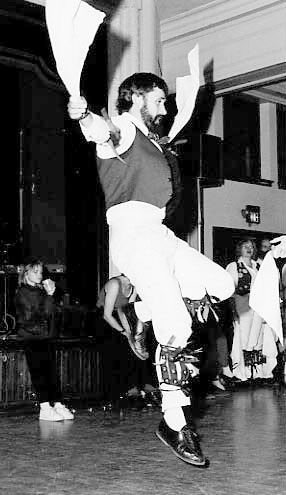

Morris

dancing (sometimes written as Morrice) is a centuries-old tradition

in England, though the roots of the dance form may be even older.

It is a very vigorous, noisy, rowdy style of dance, performed in groups

of 6-8 dancers, who wear bells on their legs and clash sticks or wave hankies.

Many dances include special leaps and jumps called capers. Morris

is considered a ritual dance tradition, rather than a social dance

tradition. As with many rural ritual traditions throughout the world,

the goal of Morris dancing was probably to bring fertility to the

land, the animals, and the people. The dances were done in the springtime

and at other special holidays, and the noise of the bells and sticks

was thought to wake up the Earth. Sweeping movements with the hankies

may have been an effort to chase away evil spirits. High jumps may

have been intended to encourage the crops to grow higher. Even the

costumes bedecked with ribbons and flowers suggest springtime and

fertility.

dancers, who wear bells on their legs and clash sticks or wave hankies.

Many dances include special leaps and jumps called capers. Morris

is considered a ritual dance tradition, rather than a social dance

tradition. As with many rural ritual traditions throughout the world,

the goal of Morris dancing was probably to bring fertility to the

land, the animals, and the people. The dances were done in the springtime

and at other special holidays, and the noise of the bells and sticks

was thought to wake up the Earth. Sweeping movements with the hankies

may have been an effort to chase away evil spirits. High jumps may

have been intended to encourage the crops to grow higher. Even the

costumes bedecked with ribbons and flowers suggest springtime and

fertility.

Because it was a ritual tradition, Morris dances were only taught to those individuals who had been accepted on the team (or side, as they say in England). Once on the team, a dancer might have to spend many years dancing on the "apprentice" side of the set before being allowed to dance on the "master" side. Until World War I, it was almost exclusively a male tradition. During World War I, women took it on themselves to keep the traditions going, and they have been dancing in large numbers ever since, sometimes on all-women teams and sometimes on mixed-gender teams.

Morris dancing as we know it today comes largely from the observations and records made by folklorists who visited English villages in the Cotswald region in the early years of the 20th century. In its current form, it has probably been influenced by many sources — everything from ancient pagan rituals to court customs. It continues to grow and evolve today. Morris has spread throughout the English-speaking world, and new dances continue to be created or adapted by many teams.

A Short History of the Winter Solabration / What is a Mummer's Play, Anyhow? / The Rapper Sword Dance / Morris Dancing / The Abbots Bromley Horn Dance / Traditional American Community Dancing / Schedule of Events / Top of Page

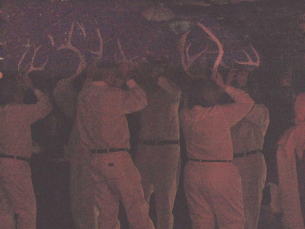

The Abbots Bromley Horn Dance is the oldest surviving ritual dance in the northern hemisphere. The dance dates back at least to the early medieval period. The first written record of its performance is from the Barthelmy fair in 1226. Historians have suggested that it celebrates the purchase of hunting rights in Needwood Forest from the Abbot of Bromley, restoring previous Saxon privileges. It is performed every year on Wakes Monday in the village of Abbots Bromley, in the English Midlands. At 8:00 a.m. the horns are taken from the church, where they are kept during the year, and the dancers make their rounds, stopping at various locations throughout the village and its surrounding farms and pubs, a distance of about ten miles. After dancing all day, the horns are returned to the church in the evening.

The

Horn Dance team consists of six Deer-men, a Fool, a Hobby Horse, Maid

Marion (a man dressed as a woman), a Bowman (Robin Hood or Boy Cupid),

and two musicians. The horns are a mystery. They are large reindeer

horns mounted on wooden effigies of stags’ heads, with the largest pair

weighing about 25 pounds. Chemical dating places them at around 1000

years old. Since there are no records of reindeer living in Britain

since Neolithic times, there is speculation that these may have been

imported especially for the dance. Three of them are painted black,

and three brown. Once they were red and white, said to represent the

battle between winter and spring, darkness and light.

The

Horn Dance team consists of six Deer-men, a Fool, a Hobby Horse, Maid

Marion (a man dressed as a woman), a Bowman (Robin Hood or Boy Cupid),

and two musicians. The horns are a mystery. They are large reindeer

horns mounted on wooden effigies of stags’ heads, with the largest pair

weighing about 25 pounds. Chemical dating places them at around 1000

years old. Since there are no records of reindeer living in Britain

since Neolithic times, there is speculation that these may have been

imported especially for the dance. Three of them are painted black,

and three brown. Once they were red and white, said to represent the

battle between winter and spring, darkness and light.

Does the dance represent a ritual combat between the forces of light and darkness? Or does it reenact a stylized hunt? In primitive societies, the miming of a successful hunt is often used as 'sympathetic magic' to give power over real quarry. The famous wall paintings at Les Trois Frères, France, known as "The Sorcerer" show a naked man dancing in antlers and a deer mask. A carving found at Pin Hole Cave, Creswell Crags, Derbyshire, (known to have been used by Neolithic hunters) portrays a man in an animal headdress. Both suggest that pre-historic shaman used animal disguises in their rituals.

According to the locals, the dance is supposed to bring good fortune to the people and fertility to the crops. In its slow and serpentine windings, is it stirring some ritual magic from a long-forgotten past? There is no way of knowing, and that is part of the enigma of the horn dance.

Although traditionally performed on Wakes Monday, the dance was also performed on other special occasions. For over 400 years now, the leadership of the horn dance has remained in the Bentley family. Although generally performed only by the men, in the 2000 dance Robin Hood was played by a young girl. The mysterious tune generally associated with the dance was first written down in 1857. The Abbots Bromley Horn Dance is reenacted for us at the Winter Solabration by the Maroon Bells Morris Dancers.

A Short History of the Winter Solabration / What is a Mummer's Play, Anyhow? / The Rapper Sword Dance / Morris Dancing / The Abbots Bromley Horn Dance / Traditional American Community Dancing / Schedule of Events / Top of Page

Traditional American Community Dance

Traditional

community dances have been part of our American culture for over two

centuries. Although they’ve waxed and waned over the years, they have

always been with us. They are the traditional contras, squares, reels,

and circle dances which your grandparents, and their grandparents, enjoyed.

They’ve been kept alive in Grange halls and church basements, in school

gyms and ballrooms, often just below the cultural radar of our news

media. They were community events, where young and old, couples and

singles, could come and participate. There were no lessons required,

or fancy costumes. All the dances were walked through so that all who

wanted to could join in. There was a band and a caller, and maybe a

potluck ahead of time.

Traditional

community dances have been part of our American culture for over two

centuries. Although they’ve waxed and waned over the years, they have

always been with us. They are the traditional contras, squares, reels,

and circle dances which your grandparents, and their grandparents, enjoyed.

They’ve been kept alive in Grange halls and church basements, in school

gyms and ballrooms, often just below the cultural radar of our news

media. They were community events, where young and old, couples and

singles, could come and participate. There were no lessons required,

or fancy costumes. All the dances were walked through so that all who

wanted to could join in. There was a band and a caller, and maybe a

potluck ahead of time.

Beginning in the early 1950’s there was a renewed interest in square dancing which evolved into the modern square dance movement, emphasizing difficult moves, elaborate costumes, dance clubs, etc. During this same time period, many of the traditional dances began to wane. In many communities, they died out, or were replaced by the club dances.

Then, in the late 50’s and early 60’s, there was a huge revival of interest in folk music in America. Many young people especially, were learning to play acoustic instruments — guitar, banjo, and fiddle. They were searching out the older musicians and learning from them. Folk Festivals and Bluegrass Festivals were springing up everywhere, along with jam sessions, sing alongs, and open stages. So what does a great fiddle tune make you want to do? Why, move your feet, of course. But the familiar rock'n'roll moves didn’t seem just right. Pretty soon, many young people rediscovered the traditional dances.

The New England contra dance was the greatest beneficiary of this renewed interest in folk music. In New England there were still many active community dances, and there were many young musicians interested in learning these traditional tunes. Soon young dancers and musicians became regulars at the local dances across New England. When young people who had learned these dances moved to a new community where there wasn't a dance, they started one. If there was a dance, they joined in. Soon the traditional square dances started incorporating more contras into their programs.

By the early 1980’s, there was a live music dance in just about every large or medium-sized city in America. And in many smaller ones. This represented a great revival for the traditional dances, but these dances were changing, too. In many cases, particularly where a new dance was started from scratch, they danced mostly contras. There were two reasons for this: First was the growing popularity of the New England contras. Secondly was the demand for new callers. When a group of dancers wanted to start a dance in a new community, they first had to find musicians. Then a sufficient number of dancers. And then a caller. Frequently the caller was one of the dancers who had learned to call a dance or two. Or one of the musicians, who wanted to make the dance succeed so that there would be an opportunity to play all these wonderful tunes for an appreciative audience. Since contra dances are much easier to learn to call than squares, these new callers started with contras. Most of the contemporary American community dances now feature more contras than squares.

These traditional dances have been tenacious in their need for live music. That’s simply part of the excitement of the event! It’s homemade, it’s traditional, it’s low tech, it’s interactive — the dancers and the musicians together making it happen. In a high tech society, it’s refreshingly old-fashioned. I think this is part of the appeal to the current generation of dancers.

— Chris Kermiet

This year’s Schedule of Events is not available yet,

but you may download a copy of the 2024 schedule here.

We expect to post the 2025 schedule mid-November.

4:45 p.m. Doors Open, Food & Wassail

5:30 p.m. Group Singing, Christmas Carols

6:15 p.m. Storyteller Susan Marie Frontczak

Bryan Connolly Extreme Juggling

7:00 p.m. Mummers Play

7:15 p.m. Grand March, followed by Traditional American Community Dances for all

(all dances will be taught and walked through)

8:20 p.m. Maroon Bells Morris Dancers Dancers,

followed by More Community Dances for all

9:30 p.m. Solstice Sword Dancers

followed by a last waltz,

& the Abbot’s Bromley Horn Dance

For more info, you may

A Short History of the Winter Solabration / What is a Mummer's Play, Anyhow? / The Rapper Sword Dance / Morris Dancing / The Abbots Bromley Horn Dance / Traditional American Community Dancing /